What is Stuttering?

Stuttering is complicated and difficult to understand, even for people who stutter. Here are two different and respected definitions of stuttering:

“Stuttering is a communication disorder in which the flow of speech is broken by repetitions (l-l-l-like this), prolongations (lllllike this) or abnormal stoppages (no sound) of sounds and syllables.”

The Stuttering Foundation of America.

“We challenge the stereotype that stuttering is inherently negative. Instead we position stammering as a different, valuable and respected way of speaking.”

Stammering Pride and Prejudice – Difference not Defect; eds: Campbell, Constantino, Simpson.

Did you know?

“Stuttering is more than just stuttering.”

J. Scott Yaruss, Professor

Michigan State University, USA

What are the basics?

- Stuttering and stammering mean the same thing

- Stuttering is caused by neurological differences

- 1% of adults stutter - 50 million people globally

- 80% are male and 20% are female

- Attitudes to stuttering vary between cultures

- Unemployment amongst people who stutter is higher and bias at work is commonplace

- Simple daily tasks can be daunting e.g. telephone calls, talking to a stranger, using fixed words

- People who stutter develop strengths including resilience, empathy and listening skills

How do cultural expectations affect people who stutter?

- The cultural expectations of most employers are for people to speak smoothly, with ease, speed and fluency

- Society looks down on different speaking styles such as stuttering, accents and tone

- “Less intelligent and lacking confidence“ are labels often attached wrongly to people who stutter

- Teasing, bullying, relationship and job rejections are all consequences of speaking with a stutter

- These barriers often result in painful feelings, including shame, self-stigma and exclusion

Audible or noticeable stuttering

- People who stutter know what they want to say

- Stuttering is individual and takes many forms – hesitations, repetitions or prolongations of sounds and words, silent blocks, and extra sounds and words

- Stuttering is unpredictable. People who stutter may speak fluently one minute and dysfluently the next

- People who stutter are no more or less nervous than anyone else. However, cultural pressures and unhelpful attitudes can make them nervous of people's responses to their stuttering

Hidden aspects of stuttering

- You cannot always hear or see stuttering

- People who stutter may switch or substitute words to avoid stuttering. This constant self-monitoring requires enormous energy and often results in a sense of dissatisfaction at not having said what they wanted to say

- Anyone who has struggled to find different words when speaking a second language may have an inkling of the effort required – yet without experiencing the shame and self-stigma associated with stuttering

- People who stutter will also avoid speaking, situations, people and relationships to avoid the negative labels associated with stuttering

- These hidden aspects of stuttering are just as disabling as the audible aspects of stuttering

It can be very hard for someone who stutters to reveal what they are experiencing under the surface.

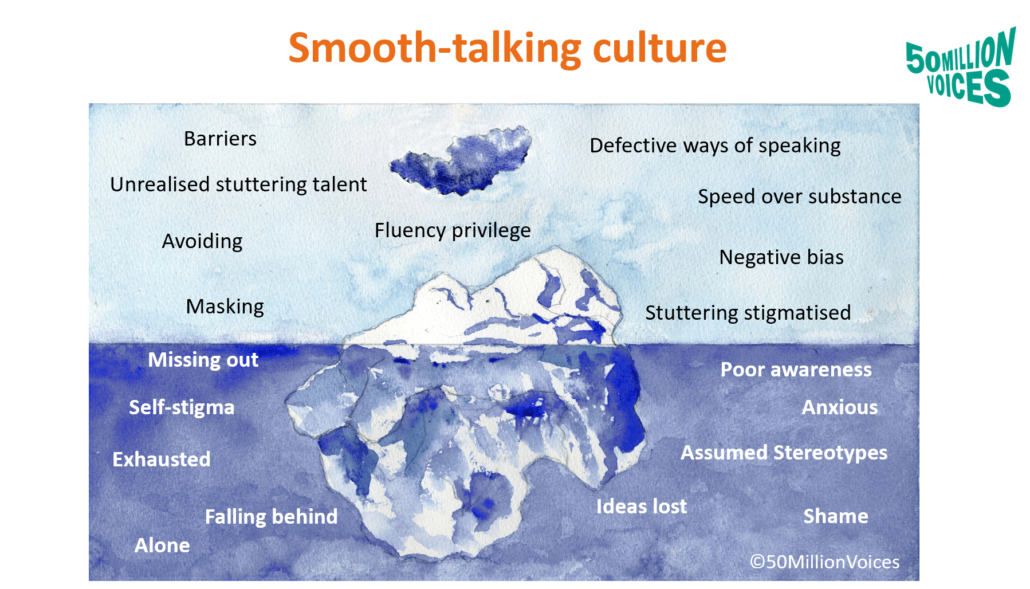

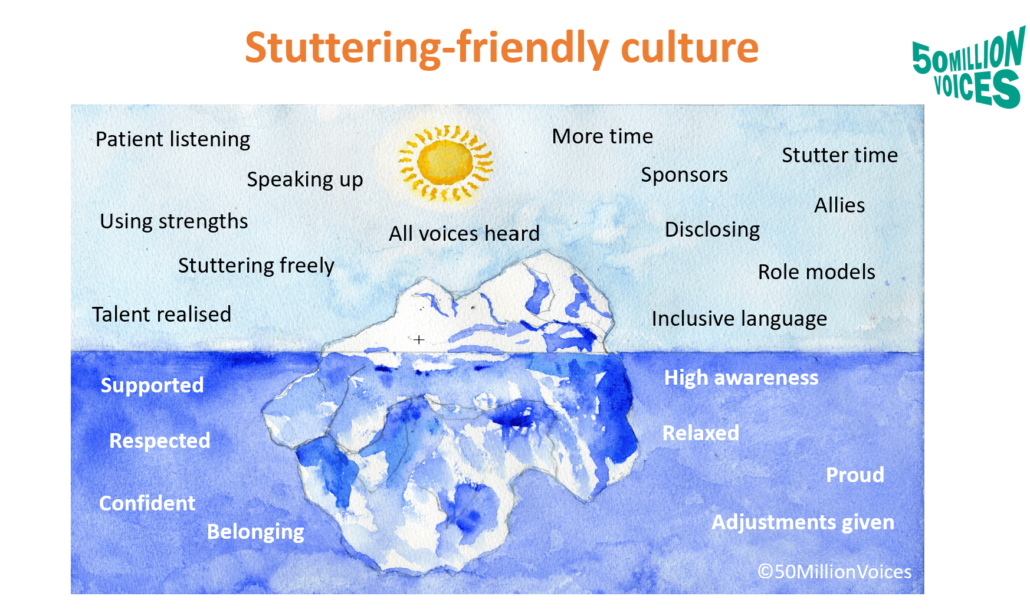

With the icebergs below representing a work colleague who stutters, these paintings highlight how their visible and invisible experience is influenced by their employer's culture when it comes to speaking:

Smooth-talking culture

Stuttering-friendly culture

Many thanks to Adam Kawecki for kindly permitting use of his artwork

“I scan ahead what I am going to say and my mind flags up words and sounds I know I may stammer on; and before I get to them I change what I am going to say to use words I know are safe. In fact, I’m stammering like crazy – you just can’t hear me doing it.”

Sir Jonathan Miller CBE

Listening

- Since 99% of adults don‘t stutter, understanding the listeners' experience is an essential part of creating a stuttering-friendly culture

- Many people feel uncomfortable when listening to a stuttering voice, especially if they are not used to hearing one

- Research shows how the brains of people hearing a stuttering voice often struggle to concentrate. This often creates discomfort for the listener

- Listeners also struggle to know how to respond to someone who is stuttering. Should they try to help with a word or stay silent? Should they maintain eye contact? Should they acknowledge the stutter?

- Listening to stuttering voices can also help us to become more patient, present and connected when we listen

Examples of zero-cost workplace adjustments for people who stutter include:

- A culture where stuttering is accepted and respected

- Awareness by colleagues of how the person who stutters prefers to communicate

- Additional time to talk in meetings, presentations and interviews

- Use of chat function in virtual meetings or written contributions in face to face meetings

- A private space to make and receive phone calls

- Flexibility to attend speech therapy during normal working hours